I make my own fingerboards which allows me to do just about anything. Here are the 4 boards for the next set of ukes (not yet trimmed for length). 3 tenors and one concert.

The black one is Richlite, a man-made material I have been using in place of ebony which is scarce, expensive, and these days is generally not completely black. Richlite is hard, very stable (we have some Richlite cutting boards that have been through the dishwasher for a number of years and they show no signs of degrading), completely black, holds frets well, inlays well, and does not involve cutting down the tropical forest.

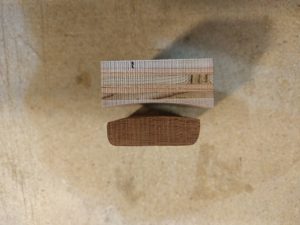

The one to the right of the black one is book-matched casuarina. I thought it would be a cool look to have a book-matched fingerboard, and this is where ‘doing it yourself’ really comes in handy. Casuarina is my new favorite fingerboard wood. It is very hard. It is #21 on the list of the 100 hardest woods in the world, as hard as the ebonys, harder than the rosewoods. It takes a wonderful polish with just fine sandpaper.

The yellow one is Florida black olive Bucida bucer which is native to southern Florida, the Caribbean, and Central America. I traded another woodworker for a chunk that is big enough to make fingerboards. Quite hard, has an intresting curl to the wood, and a really interesting color. This is going on a uke with casuarina back and sides, a ‘Florida’ uke.

The concert board is more casuarina, all heartwood this time. Lovely stuff with great properties.