(I am going to try adding to this one entry to tell a chronological story)

March 15, 2021

I have a bit of a break from commissions, so I decided to conduct an experiment. I am building three tenors, with very similar top woods but different bracing/construction details. I am interested in comparing the resultant sound side-by-side.

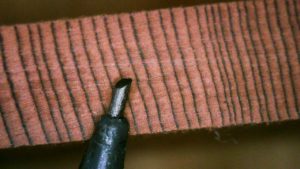

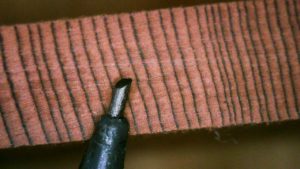

The top wood is some very fine grained redwood. Two tops are from the same board, and the third is very similar. I counted (under a microscope) 351 growth rings across the 5″ board used to make the top. Picture is of a .5mm pencil point.

The three experiments from right to left:

An X braced top – a design which is my standard, and has yielded very good results. Note, no lower transverse brace, allows more of the top to vibrate I think.

Kasha braced top – I have built some Kasha instruments, and the results have been good, but I am interested in hearing this side-by-side with the X braced top. This uses wood from the same board as the X braced top.

Double-back – I read recently about having an inner back so that the instrument back does not get damped by being against the player. There are a few builders who seem to have built double-back instruments. I have a friend with a double-back Appalachian dulcimer which is quite loud. An intriguing concept, and an opportunity to figure out build issues and do something rather different. Spruce inner back (shellac on inside of top).

March 16, 2021

The three tenors are all boxed up.

March 25, 2021

Some interesting news/data. I have gotten the fine grained redwood board dated via Dendrochronology which is the study of tree rings and the comparison of those trees rings to others going backwards in time. (A very interesting new book, “Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Rings” by Valerie Trouet. I highly recommend it. Her lab dated my redwood.) The full width board yielded 755 rings, and was accurately dated to show that it grew from 979-1734 AD. Depending on which side of the board the tops came from they are from wood that started growing in 979 AD or 1357 AD !!

April 12, 2021

The three tenor instruments are finished. All have very similar redwood tops and are all strung with the same strings (low-G). Oasis fluorocarbon for the 1’st and 2’nd strings, Thomastik-Infeld CF27 and CF30 for the 3’d and 4’th strings. All three instruments sound good (I do like a low-G setup). I am not a player so the comparisons are made by plucking open strings and listening for the differences.

Kasha vs. X braced

These two instruments have redwood tops cut from the same redwood board. It is a very fine grained and pretty stiff redwood. There is a tonal difference, but it is not a very large difference. The Kasha instrument has a bit more bass, particularly on the 4’th string, giving the instrument a bit ’rounder’ sound. As one progresses up the strings the difference between the two instruments becomes less and less, so by the first string there is virtually no difference. Sustain is the same across the two instruments. The overall difference is such that I think unless one has a very good ear (and memory) it would be hard to tell the difference if there was a 10 minute break between playing either one.

X braced vs. X braced with a double back

The short story here is that the double back seems to make no difference. Maybe the double back instrument has a bit more sustain, but that difference is well within the range of different pieces of redwood tops and/or different back & side woods. I do not think I could tell the difference when blindfolded. I do note that with either when I place my hand on the back I feel the same amount of vibration when a string is plucked so that double back does not seem to be isolating the real back.

Player comparisons

An update on comparisons of the three tenors. The instruments have had a couple of weeks to settle in, and I have had two friends who are good ukulele players come over and play the three instruments. Both of theses two friends reported the same sound characteristics. (Their preferences as to which instrument they would like to play differed however, the ear of the beholder and all of that.) Their impressions:

The X braced instrument is the brightest.

The Kasha instrument is noticeably warmer, with more low-end.

The double-back instrument falls between the X and the Kasha in terms of warmth, and it is the loudest.

Volume and sustain are very similar across all three instruments.

All in all, the instruments are different, but not wildly different. If all three were hanging in the ukulele store and you were going to buy one, there would be a lot of back-and-forth before you made your selection. (Of course they all sound better than anything else in the ukulele store!) Also, the one you pick is not all all necessarily the one your friend would pick. Factor in the different looks and it is a real toss-up.