I was running low on the kerfed lining that is glued to the side to provide a ledge, meaning expanded gluing surface, for the top and back. I make my own because few places make the “reverse” style of kerfing I use, no-one makes it in a ukulele size, and I get to use wood that is not commercially available as kerfing. I try to match the tone of the kerfing to the tone of the sides. I use a light colored kerfing (my local poplar) with light colored sides, some Spanish Cedar (kind of looks like mahogany) with brown sides, and new for this time around I made up some walnut kerfing to try out, see how it flexes, etc. It works well, and makes a nice dark kerfing for dark sides. I making a walnut baritone, and it gets walnut kerfing, so when you look inside all you see is walnut. You can’t do that with commercial kerfing.

Making kerfing however is somewhat laborious, repetitive, and not very exciting. Just one of those things one has to do, so when I get in the groove I try to make a bunch. The most mind numbing step is cutting all those little kerfs (slots) to make the strip bendable. I have a jig for the bandsaw to help, but still it is a lot of little cuts. Take a break every now and then. You don’t want to get complacent/drowsy/not paying attention around a band saw!

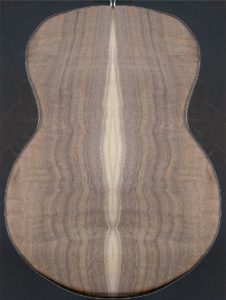

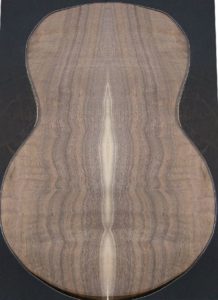

Anyway, three colors/woods of kerfing: