I bend using a silicone hear blanket, over a home-built form. Here is basically how it is done.

I wrap the side (or in this case a set of binding) in brown paper. I wet the paper, and wet the side, and then roll them up. This is then rolled up in some aluminum foil to help keep the moisture in during the bending process.

Then one puts together the ‘sandwich’ which is a flexible stainless steel slat, on top of which goes the wood, then the heating blanket, and finally another flexible stainless steel slat.

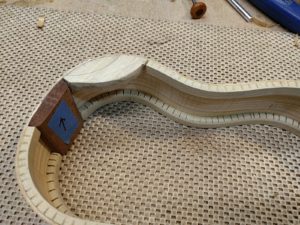

This sandwich is then put onto the bending form. I start the bend from the end, rather than the middle as some people do because by doing this I get a very good registration of where the end of the side lies, which means that the book-match on the end of the instrument is as good as it can be. So the sandwich is stood up on the end of the bending form, and the clamp tightened down. All ready to turn on the heat. Notice the surface thermometer used to monitor how hot things are.

Turn on the blanket through the controller, and let things heat up. As they get up to around 250 degrees Fahrenheit things begin to get soft, and the bend starts by itself due to the weight of the sandwich.

One then puts on the clamp for the waist, and tightens things down slowly, hoping that one does NOT hear a crack! Attach the handle used to roll down over the upper part of the side and bend it down. This handle is a dowel with a piece of loose copper pipe and is attached with fairly strong springs, so it is just a matter of slowly pulling the whole thing down over the curved form.

Put on the upper side clamp, and you are all done

I let thing ‘cook’ for 5 minutes at around 280 – 300 degrees to set the bend, then turn things off and let it cool.