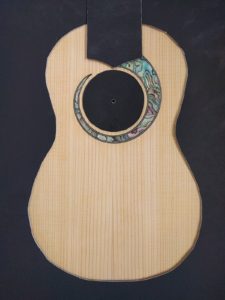

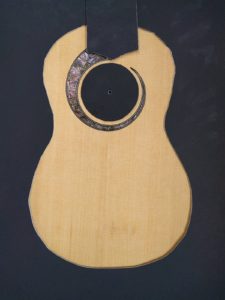

#46 is a parlor guitar, and has a standard asymmetric rosette in pink abalone (Haliotis corrugata) which is my favorite type of abalone. It varies between mostly green and mostly pink. I go through the box and pick out pink pieces to go with the redwood top and the black-red-black purfling. Here is a little synopsis of the process.

First mark the center of the sound hole and drill a 1/8 inch hole. This will be the pivot hole for for cutting the sound hole and the inner band of the rosette channel. Then, using a jig, drill another hole 3/16 of an inch down on the top. This will be the pivot hole for the outer band of the rosette.

Here is the inner band

The bands are cut using a jig I designed to fit the Steward-MacDonald Dremmel router base. This jig allows me to cut exact circles, of exactly repeatable sizes, with no adjustments. It rides on a 1/8″ pivot pin, and the difference between one hole and the next (they are all numbered) is 1/16 of an inch increase in the diameter of the circle cut.

Moving to the second pivot hole, cut a larger circle, resulting in the basic asymmetric rosette.

They clean out the rosette by using a series of smaller holes in the router base.

I pre-bend the purfling by wetting it and pressing it around my rubber cement can. Works perfectly. I have not broken a piece yet.

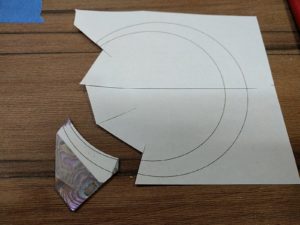

Cut two pieces of purfling to go around the inside and outside of the rosette, with a little extra so that the final fit can be done when most of the pearl has been inlayed. To cut the pearl using Corel Draw I offset two circles of the actual diameters by the 3/16″ offset of the pivot holes, account for the thickness of the purfling, and then print out a pattern. Parts of this pattern are then pasted to pearl pieces with rubber cement, and the piece is cut out along the printed lines.

The tapered pieces are then put in the rosette by putting them in the wider part and sliding them up into the taper. One wants a really tight fit. If the piece is a little large, file the edges down just a little so it goes in. It is important to keep the ends flat, so that one piece can be mated to the next piece with no gap. When you get most of the pearl in place, then you can trim the ends of the purfling so that the ends fit together tightly to make an invisible joint.

When you get nearly done, there is one last piece. This is the tricky one because it has to fit exactly on both ends. File a little, test, file a little, test, ….

When the last piece is in place, flood everything with CA glue to glue things in place and harden the purfling. Then sand it all flush with the top and you are all done.